Anticipation, Restraint, and Care

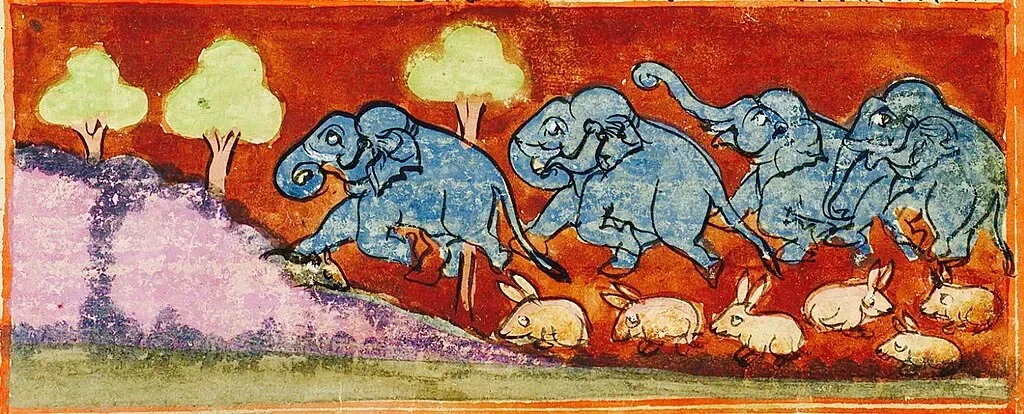

18th century watercolor of a herd of elephants, Rajasthan (Wikimedia Commons)

You may know this already, but in case you didn’t, the American child of traditional, Indian immigrants is forever pulled in two opposing directions—like a minnow who has swallowed two baits from two different fishing lines. She could not choose, so she gobbled both and is now yanked from one side of the bank to the other, in a kind of tug-of-war between individualism and collectivism.

During times like these I wish I could ask my parents for guidance, but alas, they were the children of 1960s South India where one’s path was fixed and laden with dharma, or duty. My dad deviated from the norm a bit—he loved rock climbing, so his adventures led him slightly astray—but he, too, ultimately, walked the path of dharma. My parents—the same caste and class—got married at an acceptable age, moved around India for work, and settled in America with two kids.

My life and its challenges, both past and present, are quite different from theirs. Of course, my immigrant community taught me a sense of dharma but, living in America, I also tasted individual freedom. I explored what to study, where to live, who to befriend, who to marry, and what to pursue in my career. I sit at the intersection of family, society, and self.

Living Together

Since college, I have not lived alone. I moved from co-operative housing to family homes, from eclectic shared houses with artists and musicians of all ages to pandemic-era domesticity with my parents, sister, brother-in-law, and newborn niece. Each phase carried me through a different version of communal life, eventually leading me to my current home in North Beach.

The different homes required varying degrees of patience, grace, selflessness, and good faith. Wouldn’t it have been easier—smoother, cleaner—to live alone? Perhaps, but I see intrigue in the messiness of human cohabitation. It also gets easier with discipline. For example, the more patience and grace I give myself, the more effortlessly I give patience and grace to others.

My preoccupation with collaboration and interdependence scales to the biggest projects in our society—public infrastructure, education, healthcare, housing, and, in essence, democracy. For any form of socially progressive innovation to occur—such as Khan Academy (my current employer) or Wikipedia (my former employer)—or for grassroots movements to be successful—Black Lives Matter, MeToo, Occupy Wall Street—human beings need to know how to collaborate harmoniously and sustainably.

In many Asian cultures, it is the default to think of others. This is warped by gender and class dynamics, so it is often Asian women who greatly shrink themselves down. Nonetheless, I find the intentional shrinking of self to be noble and necessary for true collaboration. In our small, joint family, there were moments where we chose to let sleeping dogs lie, and it held our family together. Perhaps I am lazy, or tired from remote work and professional communication, or delusional in assuming that—after a while— people who live interdependently can actually “just get each other”. Yet I feel in my bones that anticipation and intuition is its own ethic.

Joint Families in India

In India, and in Hindu society specifically, the joint family is the default condition. It consists of grandparents, a son, a daughter-in-law, and grandkids. The grandfather is the head of the household, and with control of the household comes control of property. A good Hindu son is one who stays home and serves his parents, and a good Hindu daughter marries into a family and serves her in-laws.

On my mom’s side, the joint family consists of my grandfather, grandmother, grand-uncle, grand-aunt, two uncles, one aunt, and two cousins. On my dad’s side, my grandfather, grandmother, uncle, aunt, and cousin live together. Both joint families are functional because everyone is playing their part. Those at the top of the hierarchy sacrifice less, but, as I have observed, no one gets by unscathed. Some form of sacrifice via tiny, invisible gestures is absolutely necessary and when those gestures peter away, the threads of the family come loose.

Every summer when I visit India, I stay with my joint families and am lovingly absorbed into the structure of the household, but undoubtedly, there is a structure to abide by. Knowing when to obey versus break tradition is not easy when you value relationships. Sometimes I choose relationships over ethics. Other times, I choose ethics. It is a constant, unending dance.

Urbanization and Westernization in India are eroding the joint family. A joint family cannot thrive if its young people want the same freedom enjoyed by many in the West. This is a concern of the Hindu right and, ironically, my own, but there is a divergence, I promise. From what I have seen and experienced, a joint family provides a sense of belonging and social safety. When it is fair to all, it can be the building block of a society. However, in many, including my own, the lack of agency for women is staggering. I personally insisted to my cousin that she not move in with her in-laws for such reasons. Therein lay the predicament of the human and feminist condition. We need one another, and we need one another to behave.

Exhausted by Communication Culture

Many years back, while living in a co-op, I struggled with a culture of over-communication. “But that’s their culture,” I thought, and so I abided by norms that I disliked. I disliked when others expounded on the physical or emotional labor they had done for me, or when asked if they may touch my possessions or enter my room. It felt unnatural. I drowned in a tsunami of explicit, therapy-like communication. Possibly, they were trying to make interdependence work but were not raised in interdependent cultures and, therefore, required incessant communication and, much to my discomfort, confrontation.

I preferred then, as I prefer now, for communication to include body language, facial expression, tone, and shared context. I want to live in a culture of emotional and social intelligence where folks know how to read between the lines and have observed one another well enough to anticipate needs. For example, I know that my husband and roommate cannot read my mind but I expect from them a high degree of intuitive behavior because—per my view—I am constantly intuiting their feelings and needs accurately.

Modern American life, liberal or conservative, teaches us to center ourselves too aggressively. In San Francisco, this can look like career ambition. Not all, but many, are in hot pursuit of career success. Relationships with others, the self, and the earth be damned.

It can also look like the hot pursuit of moral purity.

Most invisible of all is the rugged individualism that breeds amid technology-enabled convenience. You need no friends to help move furniture, family to cook you meals when sick, or a neighbor to drive you to the airport. You have TaskRabbit, DoorDash, and Uber for all that. But in truth, we are responsible for so much more than ourselves.

It feels good to have reshaped and continued a practice my family has handed down to me. A home requires patience and discipline, but what else can one expect when carrying the weight of ancient wisdom?

*This article is being reproduced with permission. See the original article on Substack.

*The opinions of contributing writers are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of We Are One Humanity. Submissions offering differing or alternative views are welcome

How Others Respond to Trump