What the Epstein Files Say About Our Culture

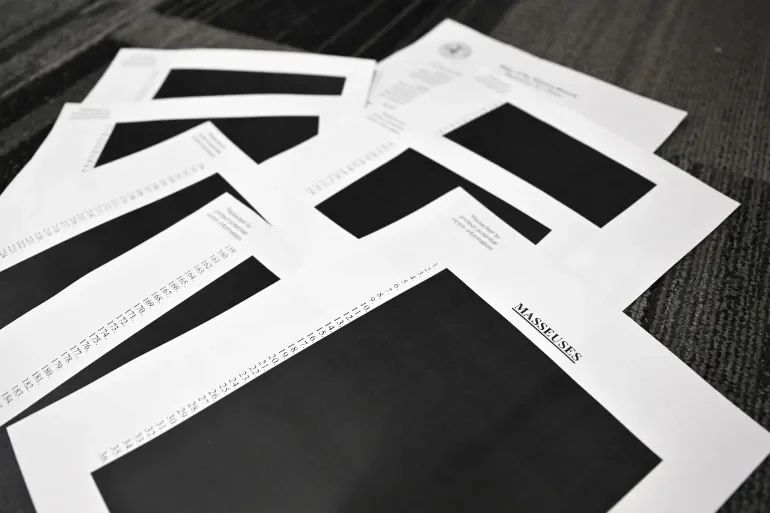

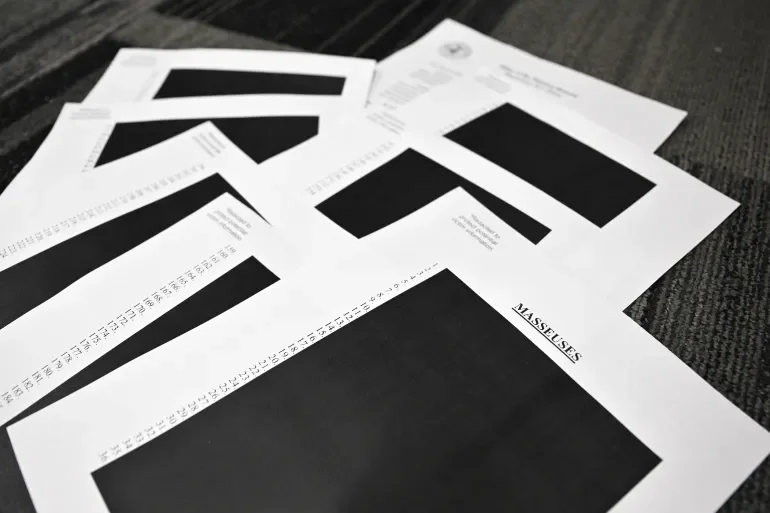

Heavily redacted pages from the Jeffrey Epstein files (Photo originally published in Al Jazeera/Mandel Ngan/AFP)

"Saw your name in the Epstein Files."

That was the subject line of a cold email that went viral last month; the screenshot was shared thousands of times across social media with gleeful admiration. "I need to hire whoever wrote this," one user on Thread posted. "Not for their product. Just for the audacity." The original tweet has since been deleted, but it is symptomatic of the fact that, in 2026, one of the largest criminal justice scandals in American history has become a punchline, a marketing tactic, a meme.

On January 30th, the Department of Justice released over 3 million pages of documents related to Jeffrey Epstein's sex trafficking operation. The files included hundreds of thousands of videos, images, and emails over two decades, and an FBI network diagram mapping his web of victims and enablers.

The public response was immediate and voracious. Custom search tools such as Jmail emerged within days, designed to let anyone browse Epstein's emails as if rifling through his inbox themselves. Subreddits roared with visualizations of Epstein’s flight mentions, his gaming preferences, and his home theater setup. Twitter threads catalog the famous names. TikTok analyzed his Amazon purchases. We are consuming the Epstein files the way we consume reality television: obsessively, communally, and with a strange mix of horror and entertainment.

But somewhere between the memes and the metadata, we lost the plot. These aren’t props made for a true crime show. They're evidence of decades of sexual abuse of minors, enabled by a network of power that has faced virtually no accountability. The reaction reveals a culture that has learned to process horror as content, institutional failure as inevitable, and paralysis as humor.

There is an unsettling magnetism to the Epstein files—not because of what he did, but because of how effortlessly he did it. His emails are shockingly casual: misspelled, grammatically challenged, written with the same self-amused tone whether arranging dinners with world leaders or ordering a "fresh batch of muffins."

Billionaires responded to his texts as if he were a college friend. Oil tycoons asked him for medical advice to treat their daughter. Diplomats and politicians were invited to his dinners.

This is the dangerous allure: the files offer a voyeuristic glimpse into how power actually operates. These hastily-written emails make elite power feel knowable, almost relatable. And that immediacy and intimacy are precisely what make it dangerous to consume as entertainment.

But the fascination runs deeper than voyeurism. The Epstein story taps into something foundational about American mythology: the belief that success is earned, that the rich deserve their wealth, and that the powerful rose through talent and hard work.

Epstein's backstory is redolent of the classic American Dream narrative: bootstraps, hustle, networking, self-invention. Born into a working-class family, he began as a teacher at an elite school in Manhattan and leveraged his connections to eventually attain extreme wealth. And that narrative is what gave him cover.

Once you're "successful," people assume you deserve it. They assume your wealth signals virtue, intelligence, discipline, and vision. It's the classical halo effect: success in one area makes us see competence everywhere else, transforming scrutiny into envy.

Epstein weaponized this. He was the self-made man, the brilliant outsider who cracked the code of wealth. And because we've been taught to worship that story, we granted him legitimacy. The emails reveal this clearly: Ivy League deans sought his funding, politicians attended his parties, and academics welcomed his half-baked "ideas" about everything from evolution to artificial intelligence, despite his having no credentials in any field. His massive wealth and thus unquestionable merit meant his judgment and input went unquestioned.

On some level, we've always known. That's why the most damning reaction is the shrug of powerlessness.

"We knew this already," this one Redditor wrote on a post. "Nothing will change." A Reddit user observed in the same thread: "People have been desensitized. I'm in 11th grade, and some people in my class are laughing about it. I think society as a whole is just screwed over mentally."

This is what the late theorist Mark Fisher called "capitalist realism": the widespread sense that the system is so resilient to change that any change feels impossible and naive. We can imagine the apocalypse more easily than we can imagine Epstein's co-conspirators in handcuffs.

And the evidence suggests we're right: Ghislaine Maxwell is the only person imprisoned in connection with Epstein's crimes. She's serving 20 years for sex trafficking and conspiracy—not as the architect, but as the accomplice.

We're not desensitized. We're exhausted. Exhausted from knowing that merit is a myth that the powerful camouflages themselves under, and that justice can be bought off. The Epstein files confirm what we already suspected, and confirmation without consequence is just spectacle.

So we scroll and make jokes, because jokes smooth over the rage, and rage without direction burns you out. But every time we treat evidence of systematic abuse as entertainment, we participate in the machinery that enabled Epstein in the first place: the machinery that values spectacle over truth.

The files will eventually disappear from the primetime news. And Jeffrey Epstein's enablers—the ones still alive, still powerful, still unnamed in any indictment—will remain exactly where they've always been.

Unless we decide otherwise. Accountability requires us to name vocally and relentlessly what we are owed. Congressional hearings for everyone who appears in the files. Investigations into the institutions that platformed him. Public testimony from survivors and directing societal attention to their stories, rather than Epstein's story. The files gave us evidence. What we do with it is still up to us.

*The opinions of contributing writers are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of We Are One Humanity. Submissions offering differing or alternative views are welcome

On silent grief, institutional failure, and the loneliness we don’t talk about