Bridging Polarization Through Engagement

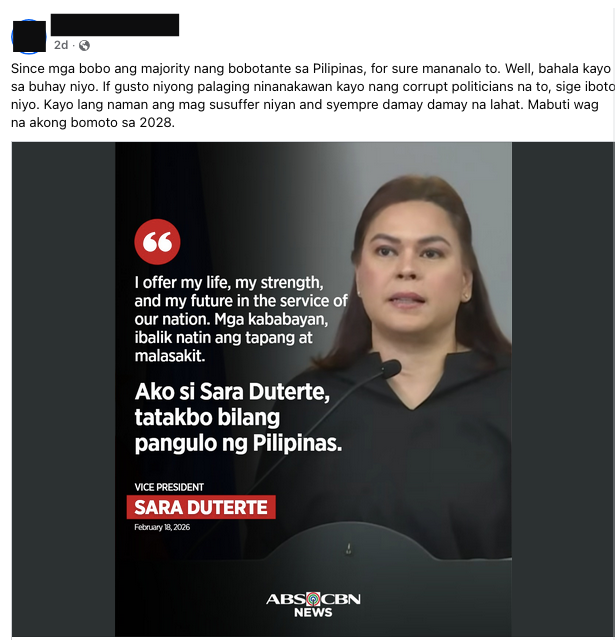

A Facebook post sharing the announcement of Philippine Vice President Sara Duterte's candidacy for President in the 2028 elections. The caption reads: "Because voters in the Philippines are dumb, she'll win for sure. It's up to you. If you prefer to be robbed every time by these corrupt politicians, go ahead, keep on voting for them. You're the ones who'll suffer anyway, and of course, you'll drag us down with you. I'd be better off if I just don't vote in 2028."

In today’s world, where social media algorithms fragment audiences into echo chambers, the tried-and-true approach to engaging communities has reemerged as a necessity.

As I write this, Philippine Vice President Sara Duterte has announced she will run for president in the 2028 national elections.

Sara is the daughter of former President Rodrigo Duterte, currently detained at the International Criminal Court in The Hague for alleged crimes against humanity linked to his war on drugs that killed tens of thousands.

Sara enjoys immense popularity. So does her father, who was even voted mayor of his bailiwick Davao City last year. His son Sebastian, who won as vice mayor of the same city, now acts as caretaker, performing the elder Duterte’s official functions in his absence.

It may boggle the mind why the Dutertes, despite all the issues surrounding them, still command such strong and widespread support. And this is not only among Filipinos living in the Philippines. The most vocal supporters are in the diaspora.

The Rise of the Dutertes -- and My Growing Despair

The rise of the Dutertes to national power is the most polarizing phenomenon in Philippine society that I have witnessed. Ten years ago, I was with ABS-CBN News covering Rodrigo Duterte’s presidential campaign. He was painted as a reluctant candidate who couldn’t care less if he would win or not. He defied all semblances of decorum, statesmanship, and diplomacy: he used profane language, he didn’t conceal his sexism that often crossed over to misogyny, and he cursed at the Pope and President Obama. Heck, he even taunted North Korean President Kim Jong Un as being “chubby.”

The crowds loved him. Online trolls amplified Duterte into this almost mythical being, drowning out any attempt at real discussion of issues. When he became president, corruption allegations surfaced and bodies of alleged drug users and pushers started piling up. But each time he dodged accountability with yet another wild story or another human rights violation, he got bolder.

My conviction in journalism began to erode. For the first time, our months-long investigations felt futile. Public outrage never materialized. We blamed the paid hacks, the digital platforms, our broken education system. The term “bobotante” was born -- a play on the Tagalog words “bobo” (dumb or stupid) and “botante” (voter). “Bobotante” was the dumb voter -- the unthinking masses easily swayed. The term gained traction among those that supported the opposition. Those labeled felt dismissed by the elite who looked down upon them. The divide became wider and sharper.

A Global Pattern Rooted in Neglect

I thought this seemingly hopeless situation was unique to the Philippines – but elections across multiple countries have shown similar patterns. In cases like the Brexit referendum in the UK, elections in Latin America, the U.S., the EU, and parts of Asia, poor governance has frequently been blamed on “ignorant,” “misinformed,” or “duped” voters.

By late 2022, I had moved to an international nonprofit that gave me the opportunity to engage with communities in different parts of the country and the world. In many of those conversations, I discovered that what we dismissed as a mere product of disinformation was rooted in people’s lived experience.

From what I heard, decades of neglect had conditioned many people into thinking their votes did not matter because they have seen politicians come and go, yet their situation remained the same. When they were labeled as unthinking, it reinforced the narrative that they were outside the circle of decision-making.

Political research on the Philippines argues that polarization isn’t adequately explained by “false narratives” alone; it is also conditioned by long-standing grievances and competing identities shaped by how people experienced democracy itself.

Facing humiliation from labels like “bobotante,” people protected themselves the only way they could: through withdrawal, silence, cynicism, or hardened identity loyalty.

Journalism Needs to Change

Duterte and other populist leaders capitalized on this frustration, presenting themselves as an alternative—however illusory—to the establishment.

I was struck with this realization: It wasn’t that journalism was meaningless. It was our approach that needed to change. We had always treated communities as subjects -- telling their stories, then moving on, our work seemingly done.

This sparked deep introspection. Had I, as a journalist, unwittingly fueled that sense of hopelessness, eroding trust in institutions among the very public I vowed to serve? There had to be a better way. Journalists could no longer afford to detach from the communities we’re meant to serve.

So I returned to my roots in community development – my undergraduate focus and the work that shaped my early career. It’s a practice grounded in immersion and in truly being present. It means actively listening to the people we serve, engaging them directly, and empowering them to shape decisions in ways that genuinely affect their lives.

In today’s world, where social media algorithms fragment audiences into echo chambers, this tried-and-true approach to engaging communities has reemerged as a necessity.

The media no longer sets or shapes the public agenda. Communities have ceased to be mere content mines. Our job isn’t about telling stories louder -- it's about listening better and turning community wisdom into shared action, without compromising accountability.

Engagement journalism flips this equation: The community becomes co-authors of the public agenda, where their lived experiences count as knowledge.

Proven Impact

Studies show engagement journalism works. A training program by U.S.-based journalism network Democracy SOS cut "horse race" coverage by half and tripled community stories (from 6% to 27%) leading to less divisive reporting. Resolve Philly’s Equally Informed program reportedly boosted trust as residents co-created stories and felt heard as experts. A Carnegie research found local news cuts partisan bias.

In this time of extreme polarization, engagement journalism offers a way forward. Rooted in humility, not naivete, it stays non-antagonistic and intentionally constructive. It cuts humiliation, widens participation, and never surrenders accountability.

*The opinions of contributing writers are their own and do not necessarily represent the views of We Are One Humanity. Submissions offering differing or alternative views are welcome

On silent grief, institutional failure, and the loneliness we don’t talk about